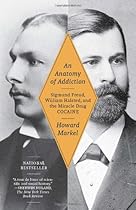

An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the Miracle Drug, Cocaine

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | 4.89 (817 Votes) |

| Asin | : | 1400078792 |

| Format Type | : | paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 336 Pages |

| Publish Date | : | 2017-10-08 |

| Language | : | English |

DESCRIPTION:

His articles have appeared in The New York Times, The Journal of the American Medical Association, and The New England Journal of Medicine, and he is a frequent contributor to National Public Radio. His books include Quarantine! and When Germs Travel. Markel is a member of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences and lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.. Howard Markel, M.D., Ph.

"Genius is not found in a bottle, pill, or potion." E. Bukowsky In Howard Markel's "An Anatomy of Addiction," two renowned figures are attracted to "a miracle drug" that reduced appetite and the need for sleep, sharpened one's focus, relieved depression, and induced a feeling of euphoria. It also had anesthetic properties that could be useful for surgeons performing dental or ophthalmological procedures. Both Sigmund Freud, the pioneering psychoanalyst, and William Halsted, one of the greatest surgeons of his time, were fascinated by this drug and d. Barbara S. Reeves said A study of the diabolical power of cocaine!. "An Anatomy of Addiction" by Howard Markel examines two famous doctors, Sigmund Freud and William Halsted and their addiction to cocaine. Freud, who invented psychoanalysis, the search for self-truth, became convinced that cocaine was a miracle drug with no side effects. Halsted, considered to be the father of modern surgery was probably the first cocaine addict to come to the attention of medical professionals in the United States. Peruvian Indians on the eastern slopes of the Andes ha. "Insightful and Credible -" according to Loyd Eskildson. Both Sigmund Freud, father of psychoanalysis, and William Halsted, originator of modern surgery, practiced medicine in the 1880s and experimented on themselves and others with cocaine's possible therapeutic uses. Freud was interested in it as an antidote for morphine addiction and as treatment for addiction, Halsted saw it as a possible anesthetic. Freud found the drug cured his indigestion, dulled his aches, and relieved his depression. After taking the drug for a few months Freud shif

This rich, engrossing book reminds us of the strangeness of even heroic destinies.” —Los Angeles Times “Markel creates rich portraits of men who shared, as he writes of Freud, a 'particular constellation of bold risk taking, emotional scar tissue, and psychic turmoil.'“ —The New Yorker“A rich, revelatory new book. Markel is a careful writer and a tireless researcher, and as a trained physician himself, Markel is able to pronounce on medical matters with firmness and authority.” —TIME “A splendid history Markel is a fluent, incisive and often subtly funny writer.” —The Baltimore Sun “Provocative persuasive and engrossing.” —Salon "Compelling and compassionate a book that profoundly demonstrates the complexity and breadth of their genius a richly woven analysis complete with anecdotes, historical research, photos and pre

One became the father of psychoanalysis; the other, of modern surgery. An Anatomy of Addiction tells the tragic and heroic story of each man, accidentally struck down in his prime by an insidious malady: tragic because of the time, relationships, and health cocaine forced each to squander; heroic in the intense battle each man waged to overcome his affliction. Markel writes of the physical and emotional damage caused by the then-heralded wonder drug, and how each man ultimately changed the world in spite of it--or because of it. Here is the full story, long overlooked, told in its rich historical context. . Acclaimed medical historian Howard Markel traces the careers of two brilliant young doctors--Sigmund Freud, neurologist, and William Halsted, surgeon--showing how their powerful addictions to cocaine shaped their enormous contributions to psychology and medicine. When Freud and Halsted began their experiments with cocaine in the 1880s, neither they, nor their colleagues, had any idea of the drug's potential to dominate and endanger their lives